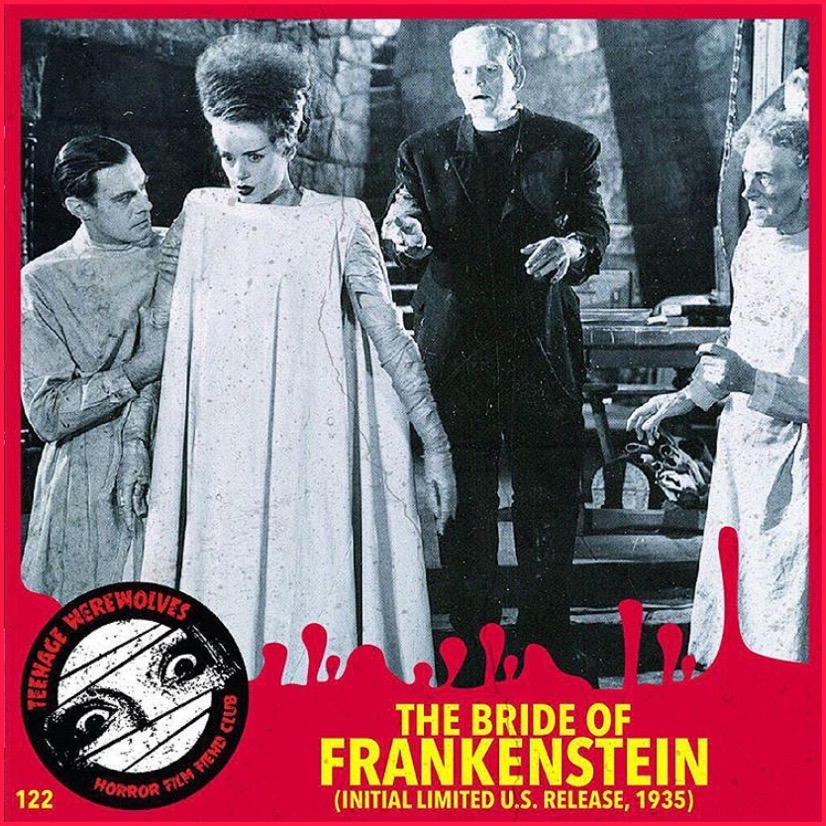

(James Whale, 20 April 1935)

“It’s a perfect night for mystery and horror!”

Though it premiered in Chicago on April 19, 1935 (and would eventually receive a full U.S. release in May of the same year), James Whale’s epic sequel, THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN came alive on this day for an initial, limited release. Often heralded as one of the few sequels to surpass its original, BRIDE is truly a masterpiece: bold, subversive, darkly comic, richly symbolic, loaded with powerful pathos, beautifully lensed, and far closer to Shelley’s source material.

Whale was initially cold on revisiting the exploits of the eponymous Monster — fearing, on one hand, that he may not be able to do justice to his 1931 film, and finding himself simply unenthused at a pointless retread, on the other — but once the rich opportunities of satire and social commentary presented themselves, Whale threw his restless creativity into the project full-force. His trademark gallows humor is placed front and center, cleverly sending up everything from Hollywood costume dramas to the Catholic church and the institution of traditional marriage itself — even the biblical crucifixion isn’t safe from Whale’s tongue-in-cheek parody and Gothic burlesque. Every aspect of this film is in fragile balance, achieving some dark magic that has rarely been duplicated, and certainly not in in a project where horror and comedy collide: Waxman’s score, packed with palpable leitmotifs; Pierce’s re-tooled make-ups; the effective, and academically expository, literary prologue; the incredible sets that are assuredly more on par with A-pictures of the era; Kenneth Strickfaden’s laboratory sequences; and the peerless cast, including Ernest Thesiger’s Dr. Septimus Pretorious and Karloff’s teenage monster, all coalesce to create an inimitable genre film that is not only influential and high-brow, but also insanely enjoyable.

The perversity in which Whale and his cast cavort with relish is surprisingly explicit — especially for 1935 — where overtones of necrophilia and homosexuality are delightfully injected into the narrative with reckless abandon, making for a more nuanced picture. The relationships between the males characters are bones long-picked over by film historians, and the impetus for this may pre-date even Whale’s involvement, as scholars have also gone at lengths to explore the ties that seemingly bound Lord Byron and Mary Shelley’s husband, poet Percy Byssche Shelley. Christopher Bram, author of Father of Frankenstein (which was eventually adapted into the Bill Condon film, GODS AND MONSTERS) posits that “Whale had a lot to do with the writing of the final script…[and] it’s clear he saw Pretorius as an old queen in love with Dr. Frankenstein. When Frankenstein’s wife walks in, his nostrils dilate and he turns away,” and a majority of he sequences within the film, including the “electric birth” of the the Bride, can be be examined through this lens. It has even been alleged that the original ending for the film made distinct implications that the heart for the Monster’s mate is that of Elizabeth, suggesting that Pretorious had clear designs on destroying Henry Frankenstein’s heteronormative relationship as part of their arcane ambitions of the scientific flesh. How exactly this played into the other sub-plots of the film — Dwight Frye’s murderous gravedigger, Carl, and the havoc his crimes have caused, especially, considering it is yet another murder from which the Bride’s heart is harvested—isn’t exactly clear. What is clear, however, is that Whale lost no time in suffusing the script with lavish amounts of subversion and sub-text (Pretorius is, of course, entirely of Whale’s design and is nowhere to be found within either edition of Shelley’s original text) and it was exact this opportunity which drew him to the project in the first place. Human relationships, however, are not the only institution to be laid upon Whale’s ________. The acerbic barbs directed at the Catholic Church, too, are of impressive note.

The interactions between the hermit and the Monster can be easily read with Biblical connotations — the bread and the wine are not lost on most viewers — and once the Monster’s world is turned from a verdant forest (complete with a bleating lamb of archetypal innocence) to a barren and blasted landscape at the hands of being shot by some passing hunters, Karloff is essentially thrust into the Christ role, when Whale replays his own version of the Crucifixion; the Monster forcibly dies for our sins, and yet he still misunderstand and fear him. Furthermore, in a sequence that did not pass the censors, the graveyard scene originally saw the Monster attempting to help a statue of Christ “off the cross,” assuming that, like himself, Jesus was a desolate and wounded being desperately in need of help…and perhaps fodder for a budding friendship. Instead, Whale redirects Karloff to brutally destroy a papal figurine with force.

Elsa Lanchester’s iconically coiffured Bride with her swan-like hissing, ensnared in the center of the diabolical toilings of men is often a classic case (along with CAT PEOPLE, ISLAND OF LOST SOULS, WHITE ZOMBIE, and DRACULA’S DAUGHTER, among others) when exploring, with a scholarly air, the mystique of the female monster. Her dual role, too, places her in the literary shoes of Shelley herself, inviting a deeper examination of the filmic text’s relation to the inimitably influential source material — we must not forget that Whale’s original adaptation from the pen of John L. Balderston strays far from the 1818, 1824, and revised 1831 narratives. The symbolic construct contained within the Bride’s final construction — that aforementioned heart that she lacks—develops considerable meaning when examined in comparison to Whale’s first film: To complete the male monster, it is a brain — logic, intellect, reason — that is necessary (though of course this results in accidental failure on the part of Fritz’s bungling), whereas the female monster’s need is satisfied by a heart — pure emotion, traditionally, distilled — creating a compelling dichotomy worthy of further discussion. Likely another of Whale’s clever send-ups, the subtext within 1935’s THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN is unending and

One of the more unique aspects of the film that, for many, set it apart from its peers (not to mention the film that both precede and follow it), is that the dread and horror initially established by the first appearances of the monster — left to rot in the bowels of the ruined mill — are actually minimized as the picture moves forward. Unlike the rat-faced Count of 1922’s NOSFERATU or even the bandaged revenant in Universal’s MUMMY films (1932-1944) whose horror seems to intensify as the film (or series) advances, our affinity for the Karloff’s Monster only grows; our fears of him are unshakably diminished, an element some find to be counter-intuitive and counter-productive. This choice on Whale’s part is, of course, heavily influenced by Shelley’s novel, however, where Frankenstein’s creation serves as a far more human counterpoint to the irresponsible and hubris-laden man whose sense of humanity has been irrevocably shed. Regardless, it creates a unusual dichotomy within monster pictures, perhaps potently adding fuel to the eventual resurgence of the Monster and his bloody brethren in the 1950’s with the Shock Theater and Son of Shock television package — an entirely new generation of monster fans were born, with a majority of them being children who could adroitly see the child-like humanity in the monster and adopted a make-up laden Karloff, Chaney, and Lugosi as “icons of misunderstood,” misfits that only the pains of adolescent maturation could match. THE BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN is, in many ways, a coming of age film, and considering that the Monster rebels against his father, challenges authority, finds his own identity through attempts at establishing peer groups and falling in with the “wrong crowd,” smoking, drinking, and learning about “girls” (which includes enduring the pain of subsequent heartbreak and rejection), making it and entirely different scholarly smoke all together when compared against other films of the era.

Few films stand this tall, Fiends, and we love it with all our hearts…and like gin, it’s our only weakness. Cheers, Creeps…here’s to a new world of gods and monsters!